Mar 4, 2013 2

The Trouble with Capitalism

When I was a student, I was a communist sympathizer.

When I was a student, I was a communist sympathizer.

I say “sympathizer” because, while I was never a Communist Party member, I was sympathetic to the critique that capitalism was a system based on exploitation and that the ends of capital were pursued by national governments in the Northern Hemisphere, in the form of colonialism and imperialism, to the detriment of people in the Southern Hemisphere and elsewhere.

(Before you accuse me of being naive about the crimes of communist regimes from Stalin to Pol Pot, please read this post. Generally speaking, I believe that one party rule is a recipe for corruption, incompetence and, at worst, outright gangsterism. I am also opposed to “utopian” politics and, in fact, see utopian inclinations in every political ideology right, left and center.)

I was reminded of these sympathies this morning while reading the New York Times (noted running dog of imperialism and propaganda tool of the CIA).

Exploitation and Disenfranchisement

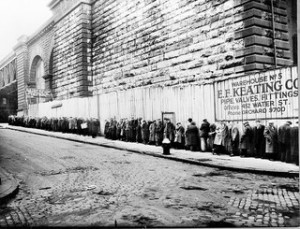

First I read that corporate profits, as a share of national income, are at their highest point since 1950, while personal income is at it’s lowest point since 1966.

As a way of explaining this state of affairs, the Times wrote:

With millions still out of work, companies face little pressure to raise salaries, while productivity gains allow them to increase sales without adding workers.

In other words, even though businesses are enjoying record profits, they are using unemployment as a hammer both to keep wages low and drive greater productivity from those “lucky” enough to have a job. If that isn’t a case of “exploitation,” I don’t know what is. (I believe that it also gives the lie to GOP contentions, dating back to the Reagan era, that policies which benefit business lead to lower unemployment and “benefit everybody.”) Read the rest of this entry »