Nov 20, 2009 5

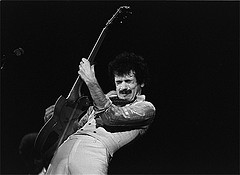

My Santana Problem

Fine. I’ll admit it. I like Carlos Santana.

Fine. I’ll admit it. I like Carlos Santana.

Not the resurgent, iPod friendly, Michelle Branch cum Matchbox 20 Santana of several years back, but the Evil Ways-Black Magic Woman -Oye Como Va-Santana of the hippie era.

Heck, I even dig the jazz-rock-fusion Santana of Love, Devotion, and Surrender and Welcome. And while we’re at it, I’ll cop to having a big soft spot for Moonflower, or about half of it anyway. There, I said it.

Why do I feel like I am herewith confessing to a regrettable aesthetic peccadillo? Because Santana is a one (or two) trick pony who plays a handful of licks with an albeit distinctively fat, warm tone, but who, when required to branch out on extended jams, quickly repeats himself and even more quickly falls back on a weird, wah-wah-fueled, ascending chromatic accelerando which is cool when you hear it for the first time as a thirteen year old but makes you shake your head when heard ever after.

Nevertheless, periodically I find myself listening to Santana, especially the first two albums and any live stuff I can dig up from the early 1970s. The Tanglewood concert on Wolfgang’s Vault is a good example of what I find compelling from this period of Santana’s oeuvre, particularly things like his frenetic but concise phrasing on “Batuka/Se Cabo.”

I think I return to this music, ultimately, because I consistently appreciate Santana’s unabashed devotion to melody, his rhythmic fluidity, and the fact that his playing frequently exhibits enough psychedelic bite to excuse me while I kiss the sky. To get a sense of what I’m talking about, check the outro-solo on “Evil Ways” where the guitar line twists and whips around like a paisley rattlesnake. My mind just blows and blows.

Certainly there is something clichéd about Santana (something which Zappa lampooned with his “Variations on the Carlos Santana Secret Chord Progression”), but it’s important to remember that it’s a cliché Santana minted and coined himself on his journey from the strip clubs of Tijuana to the patchouli soaked stages of the Fillmores East and West. He’s an icon and a dinosaur who speaks in a hilarious hipster patois that I can never get enough of, but he is also the classic example of a musician whose art is inseparable, for good or ill, from the spiritual longing that burns at its core.

I don’t know how you feel about him, but if you like Santana, you’re going to love him live in Ghana. Enjoy:

Image Courtesy of dgans.