When I was in college, I played music with a fellow named Tony Benoit. (If you’d like to read the text of an insightful and thought-provoking/action-recommending speech he gave on why we have environmental problems, you may do so now.)

When I was in college, I played music with a fellow named Tony Benoit. (If you’d like to read the text of an insightful and thought-provoking/action-recommending speech he gave on why we have environmental problems, you may do so now.)

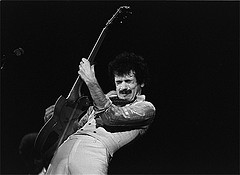

We had a lot of far-ranging conversations about truth, life, art, girls, etc., but of the many things he said to me over the years, the one that stuck in my mind’s craw was the following rebuff, apropos of what I can not now recall, “That’s because you’re a hero-worshiping guitar player.” My friend had therewith hit a certain nail on it’s undeniable head and to this day I dwell on the implications of that sobriquet.

At the time, he was probably talking about my tendency to obsess about Jerry Garcia who was, in his way, my hero. Of course, I also idolized other guitar players, Jimi Hendrix, for example, or Jimmy Page, but Garcia meant something in particular to me at the time.

I had seen the Dead a bunch of times, and I had seen Jerry’s solo band here and there, so he was actually a living person to me (though, when he was playing at Frost in 1982, his ashen pallor had a from-the-grave-ness about it). But beyond that, I, like many of my Deadhead brethren and sisthren, saw in the band, and the figure of Garcia in particular, the living embodiment of a kind of ideal. While the precise contours of this ideal are lost in a vivid purple haze, broadly speaking I would define it as an ideal, not just of freedom, but of a willingness to use that freedom to explore the outer reaches of conscious human experience.

I think, however, Tony wasn’t just talking about my ongoing idolatry of rock stars like Garcia or Dylan or Neil Young. Instead, he was highlighting a more deeply ingrained part of my developing personality. If I admired someone for being extraordinary, and, frankly, I admired Tony in this way, I would see that individual as somehow essentially different from me and consider the qualities that made them uniquely special effectively unattainable.

Tony was trying to wake me up from this delusion. He was trying to remind me that people like Jerry, or, frankly, himself, were ultimately people just like me (or if they were different from me, they were no more different than everyone is from everyone else). As he told me once, “You know, if you could get into someone’s head and live there for awhile, I think you’d find that it’s pretty much like being in your own head.” (Of course, he also said, “When I die, I’ll finally get over this hang-up that I’m different from everything else.”)

Nowadays, while I still admire folks famous, not-so-famous, and downright unknown, I no longer place them in an aspirational realm forever beyond my grasp. No, I appreciate them in their “thusness” and don’t turn this thusness into a self-esteem-withering condemnation of my own thusness.

So, thanks, To(ny).

Image Courtesy of Αλεξάνδρα.

In Ithaca, my friend Art once told me that he hated it when people spoke of “levels” as in, “We’re seeing a whole other level of play on the court today.” (I had just told him that, having finished my dissertation, I felt that I had “moved to another level.”)

In Ithaca, my friend Art once told me that he hated it when people spoke of “levels” as in, “We’re seeing a whole other level of play on the court today.” (I had just told him that, having finished my dissertation, I felt that I had “moved to another level.”)